What is the mission of the church? Answering that requires defining what we mean by the “church.” Theologians make distinctions between the universal and local church, the invisible and visible church, the institutional and organic church, or the gathered and scattered church. For our immediate purposes, I’m not interested in any of these distinctions.

The distinction we need is similar to an old Presbyterian division between the elders’ “joint” and “several” power. They say elders are authorized to do some things together or “jointly,” like excommunicate; and other things independently or “severally,” like teach. I don’t expect to revive the language of “joint” versus “several,” but that is the distinction we need for thinking about the church’s mission. Why? Because ascertaining what the mission of the church is requires us to ascertain whom God authorized to do what. To rephrase “joint” and “several,” then, I think we can say that God authorizes a church-as-organized-collective one way and a church-as-its-members another way.[1]

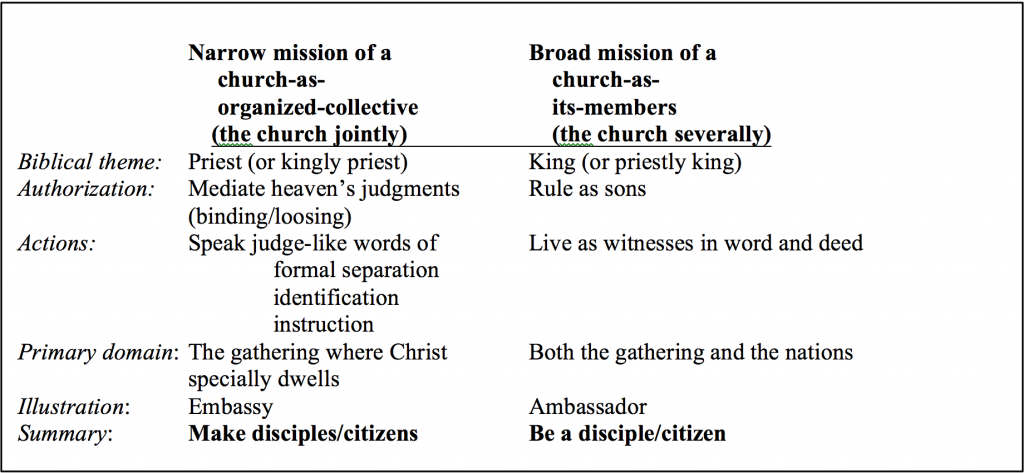

THE NARROW & BROAD MISSION

Broadly, Christ authorizes a church-as-its-members with a kingly authority to represent him as God-imaging sons and citizens, whether gathered together or scattered apart. That’s not to deny there is also something priestly about a church-as-its-members. We’re priest-kings, after all. But I do mean to put the accent on the kingly authority of ruling here.

Narrowly, God authorizes a church-as-organized-collective with a distinct priestly authority to publicly separate sinners from the world and to reconcile them to himself and his people through [re-]naming and teaching.

Very plainly, then, what is the mission of the church? The narrow mission of a church-as-organized collective is to make disciples and citizens of Christ’s kingdom. The broad mission of a church-as-its-members is to be disciples and citizens of Christ’s kingdom. The narrow employs judge-like or priestly words of formal separation, identification, and instruction. The broad rules and lives as sons of the king, representing the heavenly Father in all of life’s words and deeds. The narrow protects the holy place where God dwells, which is his temple, the church. The broad pushes God’s witness into new territory, expanding where his rule is acknowledged. For illustration purposes, we might say the narrow mission is to be an embassy, while the broad mission is to be an ambassador.

In the congregationalist conception, seeing how the two sides of the ledger work together is quite simple. Every church member, by virtue of his or her salvation, is a priest-king. Therefore every member is put to work mediating God’s judgments with the gathered church and ruling on God’s behalf whether gathered or scattered. To ask a member of a congregationalist church about the mission of the church requires specifying which hat you mean for him or her to wear: the whole-church-together hat or the church-member hat? In the presbyterian or episcopalian conception, the priestly and kingly roles work together similarly, but a greater place is given to the church officers in the “Narrow mission” column for acting on behalf of the whole church. That’s why I some advocates of the broad mission might look at the “narrow” column and regard that as the mission of the officers.

WHY THIS IS IMPORTANT

Why is it important to maintain the distinction between the church’s broad and narrow mission? First—believe it or not—for the sake of clarity. It satisfies our conflicting intuitions. When someone asks me, “What’s the mission of the church?” or “Is caring for creation church work?” or “Does the church’s work center on words or both words and deeds?” or “Is the church’s mission to care for the poor?” I need to know whether the questioner means the church as a corporate actor or the church as its individual members.

Second, the distinction protects the pastoral and programmatic priority the church-as-organized-collective should give to the narrow mission since that is its job. Several friends run a website that states in one place, “Christian churches must work for justice and peace in their neighborhoods through service.” If by that they mean that my church, Capitol Hill Baptist Church, “must” hire staff members to do political engagement or mercy ministry, then I vehemently disagree. That would bind where Scripture does not bind. If they mean that the members of Capitol Hill Baptist “must” seek justice and peace through serving others, each according to their callings and stewardships, then I entirely agree. At the moment of this writing, in fact, I am teaching a Sunday School class called Christians and Government in which I am teaching just that.

Third, maintaining a broad mission for the church severally is critical for obeying everything Jesus commanded his followers to do. It is critical for cultivating “integral” (a useful word I learned from Christopher Wright)[2] Christian lives and for warding off hypocrisy and nominalism. It keeps us from imposing a false line between the secular and the sacred for the Christian. My loving, feeding, teaching, and evangelizing my children is all of one piece.

Fourth, maintaining a narrow mission focused on adjudicatory words for the church jointly is critical for identifying the saints, equipping the saints, maintaining the existence of the local church, and maintaining the line between the church and the world. The individual Christian or church member is not authorized to do everything the whole church is, and the individual Christian needs the whole church to do its specially-sanctioned work in order for the individual to identify as a Christian and to live the Christian life that God intends.

Fifth, keeping one eye on the narrow mission keeps us eschatalogically honest. Christ has come, but the curse remains. We cannot “transform” or “redeem” anything from which the curse has not been lifted. At its worst, transformationism is a kind of disillusionment-promising prosperity gospel. Yes, the kings of the earth will bring their glory into the New Jerusalem (Rev. 21:24), as so many transformationalists today point out. But is this verse talking about Genghis Kahn, Margaret Thatcher, and Donald Trump, or about the sons of the kingdom, the saints? Either way, why not encourage Christians in their vocations through the many passages commending faith and working unto Christ, rather than speculating on one verse from apocalyptic literature? The church’s goal is not to transform the world, but to live together as a transformed world, and to invite the nations in word and deed to the Transformer.[3]

Sixth, by the same token, the distinct narrow mission reminds us to calibrate everything in our broad vocation according to the eternal possibilities of heaven or hell, destinies with much biblical support. And it gives urgency to our evangelistic witness in word and deed.

Seventh, the narrow mission of the church jointly both shapes and “brands” the whole Christian life. The average church member should not think that evangelizing their neighbor comes before caring for their own children or building good houses or being honest lawyers. But it does mean their parenting, lawyering, and building should be performed for Christ and one’s witness to Christ, as if everything we did had a fish bumper sticker on it.

Eighth, maintaining the distinction both preserves the existence of the local church and properly situates the individual Christian to a church. No one would try to blur the distinction between the law school’s mission and the lawyer’s mission. Each needs the other. Many Christians today, however, underestimate the role and distinct authority of the local church. They fail to see that the individual Christian life should equal the church member’s life and should be lived in submission to the church’s affirmation, oversight, and discipleship. When a believer harbors these mistaken assumptions, a broad mission won’t require otherwise, even if making disciples is “prioritized.” One can fulfill a broad mission apart from membership in a local church so long as one finds fellowship (with Christian friends on the golf course or at the gym?), good teaching (favorite podcast preachers?), songs of praise (car karaoke with Christian radio and my wife?), the Lord’s Supper (with a friend over dinner or at the annual Christian conference?), and doing good to all people (occasionally volunteering at the local soup kitchen or voting in elections?). The only thing that formally requires believers to join a local church as a matter of obedience—above and beyond pragmatic considerations—is the fact that the church-as-organized-collective possesses an authority the individual Christian does not possess. Take away that distinct authority and mission, and at best the local church becomes optional. If submission to the local church is a “good” not “necessary” thing, we also have to say the existence of the local church itself is a good, not necessary thing. Lest all this sounds hyperbolic, those advocating for an undifferentiated broad mission should realize that a decent-sized swath of less careful American “Christians” adopt precisely this optional approach to “church.”

On the other hand, too many so-called Christians today have learned that “church” and even “Christianity” is a one-day-a-week affair, and so nominal Christianity abounds both in the state-churches of Europe and the revivalistic and seeker churches of America. And when that’s the case the narrow definition alone will more likely appeal to them. “Leave me alone. I was baptized and prayed a prayer!”

All this is why I want to keep these two missions or jobs distinct, and then to insist that both the church-as-organized-collective and church-as-its-individual-members each do their God-assigned jobs. We need both the narrow and broad definition of the church’s mission, and we need to maintain them distinctly. Losing the broad definition tempts the Christian to separate Sunday from the rest of the week. Losing the narrow definition tempts us to let go of the local church and to downplay the significance of verbal witness and to blur the line between regenerate and unregenerate. And both errors will lead to Christian nominalism, ethical complacency, and eventually the death of churches.

Editor’s note: Taken from Four Views on the Church’s Mission by Jasons S. Sexton, general editor.

Copyright © 2017 by Jason Sexton, Jonathan Leeman, Christopher J. H. Wright, John

Franke, Peter Leithart. Used by permission of Zondervan. www.zondervan.com.

For a conversation on this topic with Mark Dever and Jonathan Leeman, check out Episode 25 of Pastors’ Talk.

* * * * *

FOOTNOTES:

[1] Notice, then, I am not making the institutional/organic distinction of Abraham Kuyper. Both sides of my distinction involve authority or an institutional element. I as an individual Christian represent Christ on Monday to Saturday at home and at work because I am a baptized, Lord’s Supper-receiving member of Capitol Hill Baptist Church. The so-called institutional church is right there with me at the dinner table or in the office all week by virtue of my participation in the ordinances.

[2] Stott and Wright, Christian Mission, 47-48, 54.

[3] See John C. Nugent, Endangered Gospel: How Fixing the World Is Killing the Church (Eugene, OR: Cascade Books, 2016), 192, 194.